Your AI Strategy Should Be 1,000 Small Bets

Why Microinnovation Beats Transformation Every Time

Somewhere right now, an employee at a large organization is building something in two days that their company has been planning for six months.

Not a prototype. Not a demo. A working tool that pulls from internal data, automates an analysis that used to take weeks, and produces results good enough to act on. They’ll share it in a team channel. A dozen colleagues will adapt it within a month. Nobody will approve it. Nobody will fund it. It will spread because it’s useful.

The six-month project, by the way, is still in requirements gathering.

This pattern is playing out across every industry right now. Finance, healthcare, manufacturing, professional services, government. A single person with access to an AI endpoint and a real problem they care about will outpace an enterprise program with a budget, a timeline, and a steering committee. Not because the program is incompetent. Because the program is solving a different problem than the person at the keyboard.

The Speed Mismatch

Enterprise AI adoption has a structural timing problem. Gartner estimates that 87% of AI projects never make it past pilot stage. MIT Sloan found that 95% of generative AI pilots deliver zero measurable return on P&L. These aren’t failures of talent or intent. Most of the people involved, from internal teams to external advisors, are genuinely trying to do the right thing.

The average enterprise AI roadmap has a 12-18 month horizon. The average foundational model generation lasts about 6 months. The math doesn’t work.

The problem is structural. Traditional transformation programs are designed for technologies that move slowly: ERP migrations, cloud transitions, data warehouse modernizations. Those projects reward careful planning because the target holds still long enough to aim at it. AI doesn’t hold still. The models change, the capabilities expand, and the use cases that seemed theoretical six months ago become table stakes.

So organizations do what they’ve always done: they plan thoroughly, align stakeholders, build governance frameworks, run procurement. All of it reasonable. All of it necessary at some level. But the cumulative timeline means that by the time you’re ready to deploy, the landscape has shifted under you. Not because anyone made a mistake, but because the cadence of enterprise planning and the cadence of AI capability development are fundamentally mismatched.

The result is a familiar pattern: pilots that technically work but that nobody adopts at scale. Not because the technology failed, but because the window of relevance closed while the organization was still getting ready.

The Bottleneck Was Never the Model

Here’s what most AI strategies get wrong at a foundational level: they assume the hard part is the technology. It isn’t. Not anymore.

GPT-4 class models have been broadly available since early 2024. Claude, Gemini, Llama, Mistral, and dozens of others are accessible through APIs that cost pennies per call. Open-source models run on consumer hardware. The capability gap between “what AI can do” and “what most knowledge workers need AI to do” closed somewhere around mid-2024 and has been widening in the other direction ever since.

The actual bottlenecks are:

Access. Can your people get to an AI endpoint without filing three tickets and waiting two weeks? In most enterprises, no. The procurement process for an API key takes longer than training the model itself.

Permission. Do your people feel safe experimenting? Or does every AI use case require a risk assessment, a legal review, and sign-off from someone who doesn’t understand what they’re approving? Permission isn’t just policy. It’s culture. It’s whether someone feels they’ll be rewarded for trying something new or punished if it doesn’t work.

Culture. Do your people share what they build? Or do solutions die in individual notebooks, never seen by the ten other people who have the exact same problem? The difference between a company where AI compounds and one where it stalls is whether there’s a mechanism for solutions to travel.

The best AI in the world is useless if people can’t reach it, aren’t allowed to use it, or don’t share what they learn.

I wrote recently about the AI translation problem, and the research is clear: information doesn’t change behavior. Participation does. You can train executives on AI all day. You can run workshops until everyone can define “retrieval-augmented generation.” None of it matters until people actually build something. The shift happens at the keyboard, not in the conference room.

1,000 Micro-Innovations

I’ve spent the last two years testing a different model. Instead of a top-down AI transformation, I built a program designed around one idea: make experimentation so fast and so safe that people can’t help but try things.

The design principles were simple:

Fifteen minutes from idea to experiment. Not weeks. Not days. A researcher has a hypothesis about how AI could help their workflow? They should be running that experiment before their coffee gets cold. That means pre-approved endpoints, starter code, example notebooks, and lightweight templates ready to go. No procurement. No tickets. No waiting.

Guardrails, not gatekeepers. Governance is essential. But governance that says “no until we say yes” is a different animal than governance that says “yes, within these boundaries.” I negotiated an accelerated approval pathway that let people experiment with approved models immediately while maintaining data protection, model risk controls, and audit trails. Safe is the fast way. You can move faster with guardrails than without them, because nobody’s afraid to touch anything.

A marketplace for solutions. When someone builds something useful, it should take less effort to share it than to keep it private. We built an internal exchange where people publish their tools, patterns, and prompts. Not polished products. Working solutions. Messy notebooks with comments like “this part is hacky but it works.” Authenticity over polish. Within a year, we had 40+ solutions available for anyone to pick up, adapt, and improve.

Champions, not training programs. Traditional AI training follows the deficit model: people don’t know AI, so teach them AI. It doesn’t work. What works is peer learning. One person in a team builds something, shows their colleagues, and suddenly the whole team is experimenting. We formalized this with an ambassador network, but the real mechanism was organic. Success is contagious.

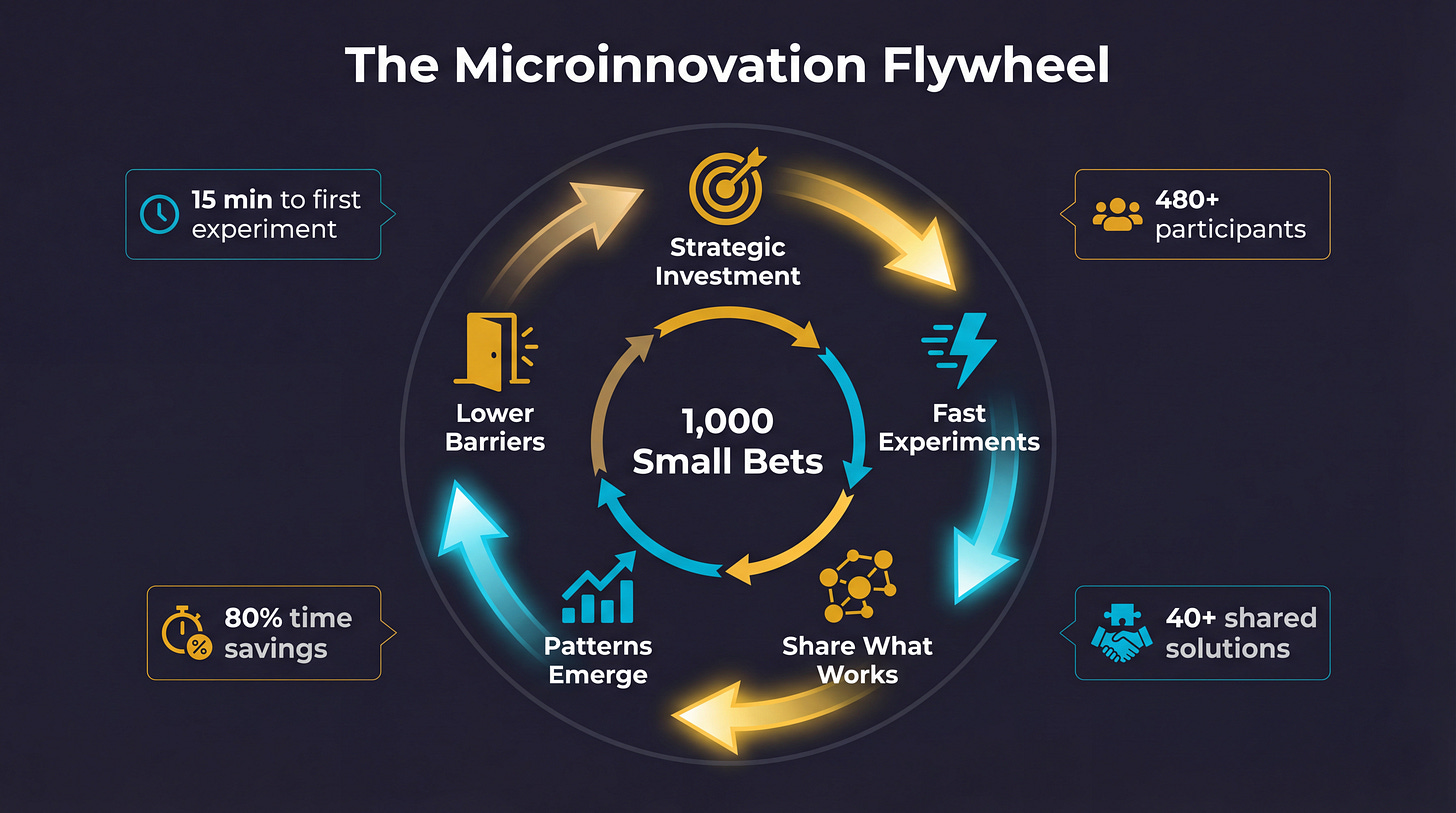

The cycle: Learn. Experiment. Share. Scale. Every solution shared saves time for the next person, sparks new ideas, and builds organizational muscle memory.

Let patterns emerge. This is the part that makes strategy people uncomfortable. We didn’t decide which use cases to prioritize. We gave people tools, removed barriers, and watched what happened. The community told us what mattered. Literature review automation emerged as a dominant pattern not because someone put it on a roadmap, but because six independent teams all built variations of it within the first three months. That signal is worth more than any top-down prioritization exercise.

What Happened

The program grew from a handful of early adopters to 480+ active participants in under a year. No mandate. No requirement. People joined because other people told them it was worth their time.

The results:

40+ shared solutions in the internal marketplace, each reusable across teams

80% time reduction in literature review workflows, independently validated across multiple research groups

15-minute median time from “I have an idea” to “I’m running an experiment,” down from weeks in the traditional IT request cycle

Zero governance incidents despite hundreds of active experiments, because the guardrails worked

But the number that matters most isn’t any of those. It’s this: the patterns that emerged from bottom-up experimentation are now informing the organization’s actual AI strategy. The big, strategic AI investments that leadership is making in 2026 aren’t based on consultant recommendations or competitive benchmarking. They’re based on what 480 people already proved works.

Bottom-up innovation through tangible micro-wins builds the foundation for strategic investment. The “big bets” become obvious once you’ve seen what sticks.

This is the flywheel. Small experiments generate evidence. Evidence builds confidence. Confidence earns budget. Budget funds the infrastructure that makes the next round of experiments even easier. It’s compound velocity applied to organizational capability.

“But You Need Both”

This is where someone raises their hand and says: you can’t just let people experiment without executive support. You need infrastructure. You need governance. You need capital.

They’re right. And the strongest version of this argument is worth taking seriously.

Infrastructure requires authority. Nobody approves GPU clusters or enterprise security policies from the bottom up. Cloud resources, compliance frameworks, data protection standards: these are leadership decisions, full stop. A grassroots movement can’t authorize multi-million-dollar platform investments, and it shouldn’t try.

Some bets are inherently strategic. Bottom-up innovation tends to optimize existing processes. A researcher uses AI to do their current job 10% faster. That’s valuable, but it’s incremental. Transformational leaps (new capabilities that didn’t exist before, new business models, entirely new categories of work) often require strategic vision and sustained investment that no organic movement can provide. In regulated industries like pharma, AI touches regulatory bodies, patient safety, and competitive IP. Engineers can’t and shouldn’t make those calls alone.

Bottom-up optimizes what exists. Top-down enables what doesn’t exist yet. You need both. The question is sequencing.

Here’s the reframe: the role of top-down leadership isn’t to dictate the innovation. It’s to create the conditions where innovation can happen safely and at scale. Set the governance frame. Fund the shared infrastructure. Define the boundaries. Then let people fill that frame with work you didn’t anticipate.

Too much top-down without bottom-up energy gives you compliance without commitment. A platform nobody asked for, mandated from above, adopted on paper and ignored in practice. Too much bottom-up without top-down cover gives you shadow AI sprawl: random tools, no security standards, duplicated effort, real risk.

The pattern that actually works is bottom-up execution within top-down guardrails. Leadership builds the stage. The people on it decide what to perform. When an engineer can’t get what they need through official channels, they build shadow systems. The solution isn’t more control. It’s better options inside the frame.

The microinnovation thesis isn’t anti-strategy. It’s a claim about sequencing. Start with experimentation. Let evidence accumulate. Then make the big strategic investments with confidence, because you’ve seen what your people actually need instead of guessing.

I think about it the way I’ve written about delegation before: the goal isn’t to automate people’s work. The goal is to give them capabilities they didn’t have yesterday and let them figure out what to do with them. People are remarkably good at this when you get out of their way.

The Counterintuitive Insight

A 60-page strategy document is a bet. It’s a bet that you correctly identified the right use cases, the right vendors, the right timeline, and the right governance model before anyone in your organization actually used AI in their daily work. That’s a massive bet with very little information.

A microinnovation approach is 1,000 small bets. Each one is cheap. Each one generates data. Each one either works (and gets shared) or doesn’t (and gets abandoned quietly, with minimal cost). After a year, you have an evidence base that no strategy document can match. And when leadership is ready to place the big bets, they’re informed by what 480 people already proved works, not by what a slide deck predicted would work.

The companies that dominate the next decade of AI won’t be the ones with the biggest AI budgets or the most sophisticated strategies. They’ll be the ones that figured out how to enable 1,000 micro-innovations, created the conditions for those innovations to spread, and had the wisdom to invest in the patterns that emerged.

They won’t have transformed. They’ll have compounded.

What This Means for You

If you’re leading AI adoption in any organization, here’s the honest version:

Stop waiting for the perfect strategy. You will never have enough information to write one. The models will change. The use cases will change. Your people will surprise you with applications you never imagined, but only if you let them.

Make the first experiment trivially easy. If it takes more than an afternoon to go from “I want to try AI on this problem” to “I’m trying AI on this problem,” your process is the bottleneck. Fix the process, not the people.

Build for sharing, not showcasing. Corporate AI demos are theater. Internal marketplaces where people share working (imperfect) solutions are infrastructure. One compounds. The other doesn’t.

Trust the signal from the ground. When five teams independently build the same type of solution, that’s a signal worth more than any market analysis. When nobody touches a use case your strategy deck said was “high priority,” that’s a signal too.

The transformation everyone is chasing? It doesn’t come from the top. It comes from 1,000 people who each found one way to do their job better, shared it with one colleague, and started a chain reaction that no roadmap could have predicted.

That’s not chaos. That’s how capability actually compounds.