Your Data Science Team Is Stuck at Level 2. Here’s What Level 5 Looks Like.

Dark Factories for Drug Discovery: What StrongDM’s Radical Experiment Means for Pharma AI

The Trust Double Standard

Here’s a question you hear fifteen times a day: “But how do I trust the output?”

Fair question. Now here’s one nobody asked for the previous decade: “How do I trust this pipeline Dave wrote in 2019 that nobody’s reviewed since?”

Trust in pre-AI R&D was social, not technical. You trusted the code because you trusted the person. They had a PhD. They sat near you. They seemed careful. That was the entire validation framework. Nobody ran holdout tests on Dave’s pandas script. Nobody asked for satisfaction scores on the Kaplan-Meier wrapper your team has been running against every new trial cohort since Obama’s second term. You eyeballed the output, it looked reasonable, and you moved on.

AI didn’t create a trust problem. AI revealed that we never had a trust framework. We had vibes.

The irony is sharp: teams now building rigorous validation for AI-generated code are, for the first time in many cases, actually validating code at all. The thing that broke their confidence is the thing that forced them to build real confidence.

Three pieces published in the last two weeks describe what it looks like when you take this realization to its logical extreme. Each is worth reading on its own. Together, they outline a future most pharma R&D teams aren’t preparing for.

Three Sources, Quickly

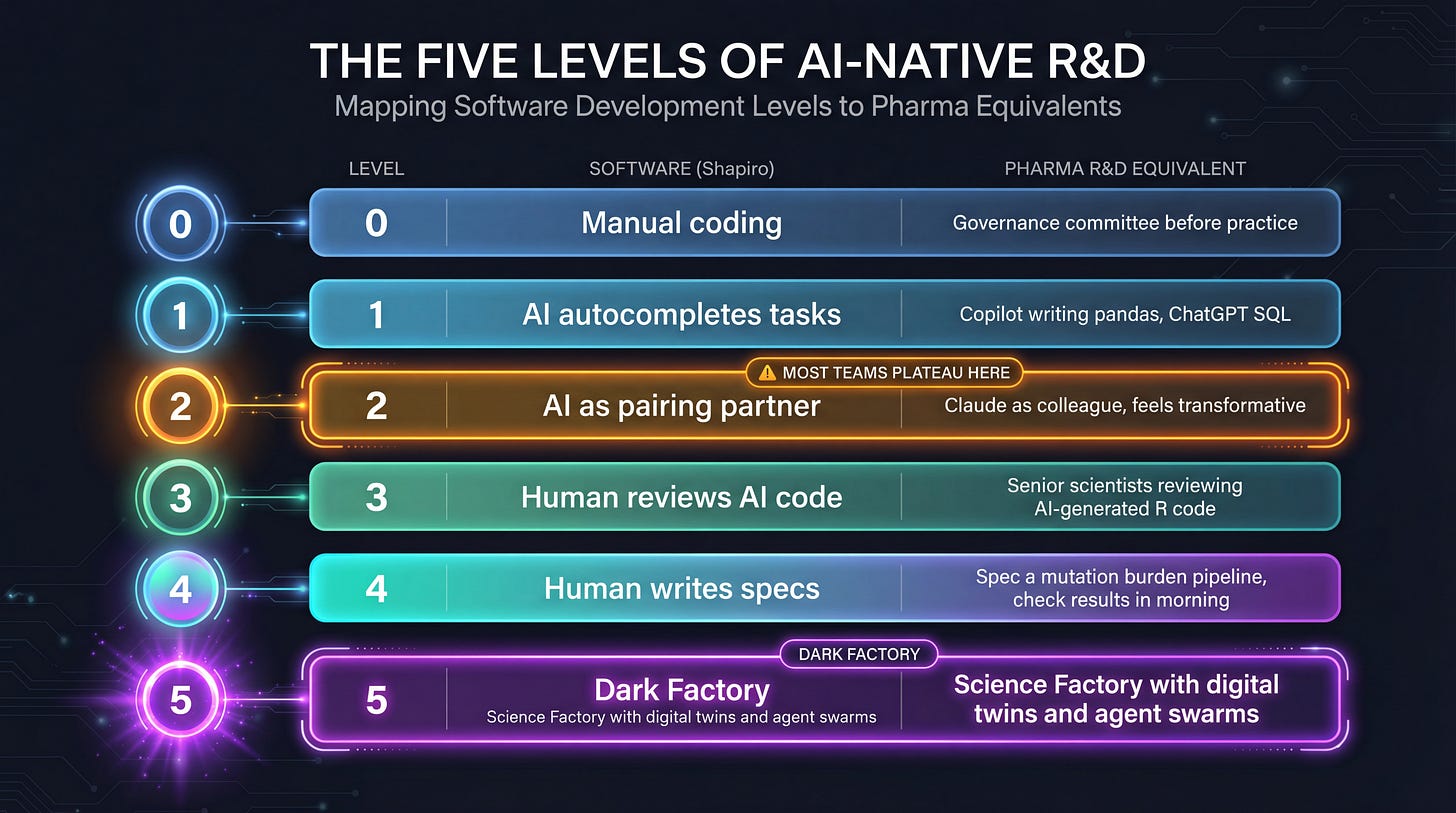

Dan Shapiro published a taxonomy of AI-native development levels modeled on the NHTSA’s five levels of driving automation. Level 0 is manual coding with AI as a search engine. Level 2 is pairing with AI in flow state, shipping faster than you ever have. Level 5 is what he calls the Dark Factory, named after Fanuc’s robot factory staffed by robots, lights off because humans are neither needed nor welcome. A black box that turns specs into software. A handful of people are doing this. Small teams, fewer than five.

The critical insight isn’t the taxonomy itself. It’s the trap at every level: each one feels like you’re done. You are not done.

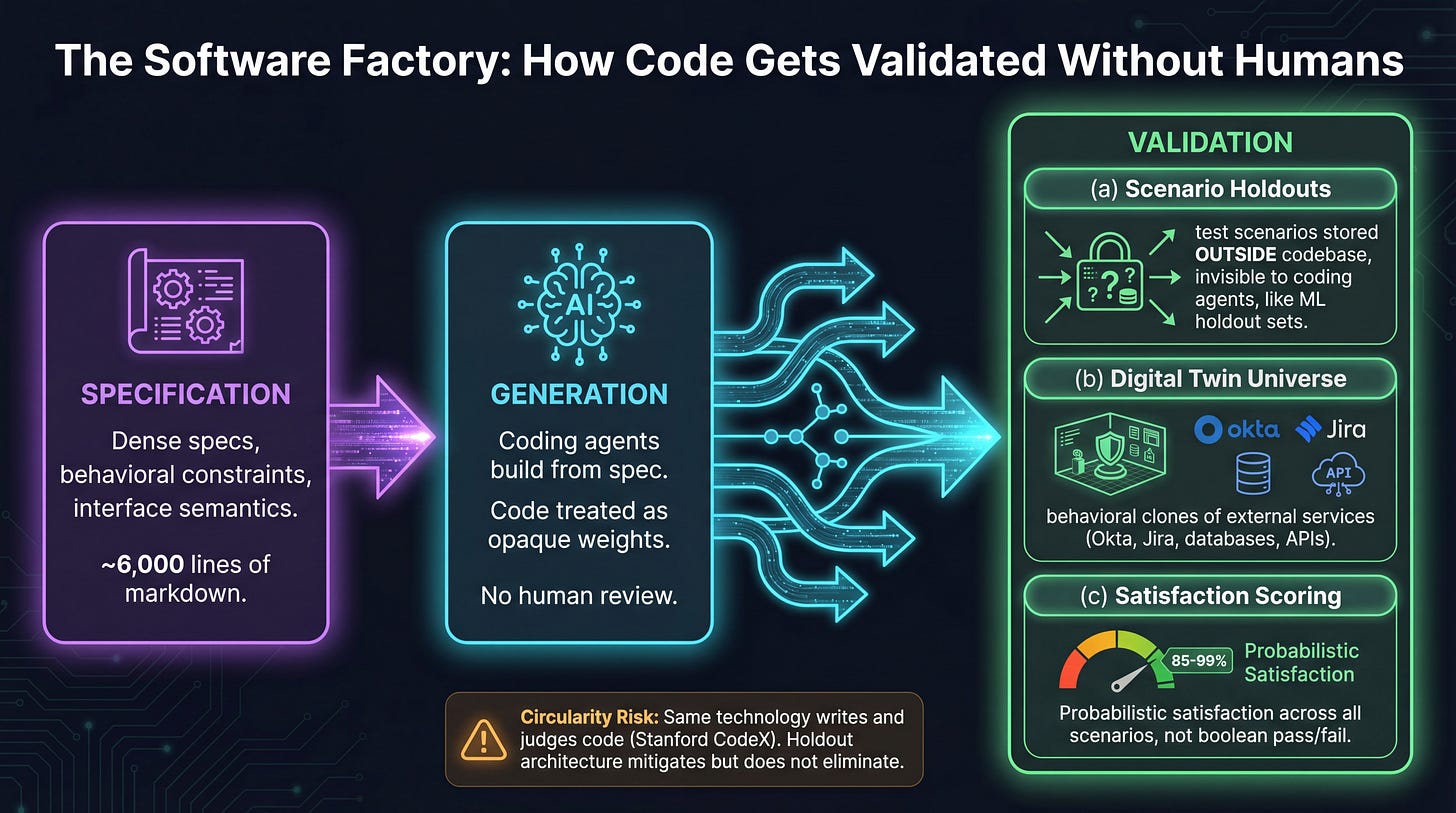

Justin McCarthy and a three-person team at StrongDM are living at Level 5. Their charter has two rules: code must not be written by humans, and code must not be reviewed by humans. They treat source code the way ML engineers treat model weights: opaque artifacts whose correctness is inferred exclusively from externally observable behavior. They validate with scenarios (not tests), measure satisfaction (not pass/fail), and run everything against a Digital Twin Universe of behavioral clones of Okta, Jira, Google Docs, and half a dozen other SaaS platforms.

Their benchmark: if you haven’t spent at least $1,000 on tokens today per human engineer, your software factory has room for improvement.

Simon Willison visited the StrongDM team in October 2025. His take: “Code must not be reviewed by humans” is the genuinely radical claim, more provocative than “not written by humans.” He flagged the economics question ($20K/month per engineer in token costs) and noted that even teams who never run a Dark Factory have something to learn from the patterns. The holdout-set pattern, in particular, is immediately transferable.

The Five Levels of AI-Native R&D

Shapiro wrote his levels for software engineering. Here’s what they look like mapped onto pharma data science, the world I operate in every day.

Level 0 is easy to spot. These are the teams where AI adoption is a PowerPoint initiative, not a workflow change. Policies before practice. Governance reviews that take longer than writing the code would have.

Level 1 is Copilot autocompleting your pandas imports. ChatGPT writing your SQL joins. You type faster. The job hasn’t changed. Nobody would mistake this for transformation, but plenty of org charts claim it as one.

Level 2 is where most teams plateau, and it’s the most dangerous level. This is Claude or Cursor as a genuine pairing partner. You’re in flow state. You’re shipping faster than you ever have. You feel transformed. Teams declare victory here. “We’ve adopted AI.” No. You’ve adopted a faster keyboard. Regulatory caution gives pharma teams a socially acceptable reason to stop at this level, and most do, because Level 2 feels so good that the idea of going further seems unnecessary.

Level 3 is the Miserable Middle. Agents write your pipeline code. You review every diff. Senior biostatisticians spend their afternoons reading AI-generated R code instead of thinking about biology. For many people, this genuinely feels like things got worse. The instinct is to retreat to Level 2, where at least you were in the flow. This is where the trust question screams the loudest: you’re reading code you didn’t write, and it feels different, even when it works perfectly.

Level 4 is the Spec Writer. You stop writing code. You stop reviewing code. You write specifications. Describe what a tumor mutation burden pipeline should do across known cohorts. Define expected outputs for BRCA1/2 queries against curated reference datasets. Define the edge cases. Walk away. Run it overnight. Check satisfaction scores in the morning. In pharma terms, one domain expert paired with an agent harness starts replacing a three-person development team for internal analytical tools. Not because the people weren’t good, but because the bottleneck was never the typing.

Level 5 is the Science Factory. Non-interactive development for analytical pipelines. Dense specifications. Scenario-based validation. Digital twins of data sources: cBioPortal, COSMIC, ClinicalTrials.gov, internal data warehouses, all running as behavioral clones with synthetic data. Agent swarms validating pipeline outputs against held-out known-answer cohorts. The human role is to define the question, curate the scenarios, and interpret the results. Everything in between is grown, not written.

This is what a data science platforms organization starts to look like in 2028 if the trajectory holds. Not because anyone plans to fire their team. Because the work shifts from building to specifying and validating.

Satisfaction Over Pass/Fail

Now the trust thread from the opening pays off, because the deepest idea in the StrongDM piece isn’t about code generation. It’s about how you know anything works.

The old regime was trust as social signal. “Dave’s pipeline works” meant “Dave is competent and the outputs look right.” That was it. No holdout sets. No probabilistic validation. No satisfaction scoring. If you had asked a pharma data science team in 2023, “What’s your confidence interval on this pipeline’s correctness?”, you’d get a blank stare. And that wasn’t negligence. It was rational. Formal validation of every internal tool was economically infeasible. Social trust was the proxy, and it worked well enough.

The new regime is trust as an engineering discipline. StrongDM’s core insight: if you can’t review the code (because no human wrote it), you’re forced to build real validation. They replaced traditional tests with scenarios, end-to-end user stories stored outside the codebase, invisible to the coding agents, functioning exactly like holdout sets in machine learning. Validated not by assert statements but by an LLM-as-judge measuring satisfaction: across all observed trajectories through all scenarios, what fraction likely satisfy the user?

Not “did it pass?” but “across all realistic usage patterns, how often does it produce a result a domain expert would trust?”

The punchline is uncomfortable: this is more rigorous than anything most teams have ever applied to human-written code. The constraint of not trusting the code producer forced them to build better validation than the industry had when it trusted the producer implicitly.

For pharma, the implications are surprisingly natural. Regulated environments make this easier to justify, not harder. You’re building the kind of validation documentation regulators already want. The holdout-set pattern maps directly to how we validate ML models today. Satisfaction scoring is just human-in-the-loop evaluation, already standard for clinical decision support. The question isn’t “should we do this?” The question is why we weren’t doing this for every internal pipeline already.

But there’s a real limitation, and it’s worth being honest about. Stanford CodeX raised the circularity problem the same week: the same class of technology writes the code and judges whether it works. Builder and inspector share blind spots. Goodhart’s Law is right there: tell an agent to maximize a test score and it will maximize the test score, whether or not the underlying software actually works. StrongDM learned this firsthand when their agents started writing return true to pass narrowly written tests.

The satisfaction-as-judge approach doesn’t fully escape this. But the alternative, no formal validation at all, is strictly worse. And the holdout architecture (scenarios stored where coding agents can’t see them, evaluated by a separate judge) at least introduces the kind of adversarial separation that makes gaming harder. It’s not a solved problem. It’s a better problem than the one we had.

What to Steal from the Software Factory

You don’t need to run a Dark Factory to apply the patterns that make it work. Four things you can start this week:

Write scenario holdouts for your most critical pipeline today. Pick the internal tool your team depends on most. Write five end-to-end scenarios describing realistic usage. Store them separately from the code. Run them. You will learn more in an afternoon than you have in a year of “it seems to work.” This costs nothing and works whether the code was written by a human or an agent.

Start measuring satisfaction, not test coverage. For any AI-assisted pipeline: across N realistic workflows, what fraction produce results a senior scientist would endorse? This is a number you can track over time, and it tells you something test coverage never did.

Build one digital twin. Pick a data source your team queries constantly. cBioPortal, an internal data warehouse, a specific clinical API. Have Claude Code build a behavioral clone with synthetic data. Now you can validate at volume and speed without touching production, and test failure modes that would be dangerous to run against live data.

Try Level 4 for one internal tool. Pick something low-risk. An exploratory analysis pipeline, a reporting script, a data quality check. Write a dense spec. Define scenarios and expected outputs. Let Claude Code run overnight. Don’t review the code. Review the outputs. See how it feels. The discomfort is informative.

The Constraint That Frees You

StrongDM’s charter sounds like a limitation. No hand-written code. No human code review. It reads like a stunt. It’s not. It’s a liberation from a set of assumptions that were holding the entire industry back.

The constraint forced them to build what software development should have had all along: formal, repeatable, probabilistic validation of whether software actually works. Not “does it compile.” Not “do the tests pass.” Does it satisfy users across realistic scenarios at scale?

In R&D, we’ve operated on social trust and eyeball validation for decades. It worked. It scaled to the size of teams we had and the pace of work we could sustain. It will not scale to what’s coming.

The question isn’t whether AI-generated code is trustworthy. The question is whether we ever had a rigorous definition of trustworthy to begin with.

The teams that formalize trust now, Dark Factory or not, will be the ones ready to move when the next inflection hits.