The Robot on My Desk Learned to Dance

An experiment in agentic AI, building in public, and holiday side projects

I bought a robot to see what happens when you build something in public with Claude Code doing the heavy lifting.

Three days later, it’s dancing to my music and we’re in the official app store.

This is the story of that build. Not a tutorial. Not a product review. Just an honest account of what happened when I decided to spend the week before the holidays experimenting with a small expressive robot and an agentic AI that writes code, runs commands, and documents everything as we go.

Why I Got the Robot

Reachy Mini caught my attention a few months ago. It’s a small desktop robot with a head that moves on a platform, two antennas for expression, and a body that rotates. Designed by Pollen Robotics in France. Hackable. Python SDK. MuJoCo simulation so you can test before you deploy to hardware.

But the robot wasn’t really the point.

I wanted to run an experiment on building in public. Not the curated kind where you share wins after the fact. The messy kind where you document everything as it happens: the debugging sessions, the wrong turns, the moments where something finally works.

I’ve been working with Claude Code for months now, and I wanted to see what happens when you let an agentic AI loose on a hardware project and capture the entire process.

The hypothesis: with Claude handling the research, the code, the debugging, and the documentation, I could build something real in a compressed timeframe while still capturing every step for others to follow.

Three days later, I have my answer.

First Boot

I assembled the robot overnight. The Lite version has nine motors: one for body rotation, six for the platform that moves the head, two for the antennas.

Plugged it in via USB the next morning and asked Claude Code for help getting it running.

Forty-five minutes later, the robot was talking back to me.

That’s not hyperbole. The daemon was configured, the motors were responding, the conversation app was installed and connected to OpenAI. I’d spent the previous week writing code in simulation, and it worked on the hardware immediately.

Claude diagnosed a sim-vs-hardware configuration issue (the daemon was still running with simulation flags), fixed a serial port locking problem, traced an API key validation issue through library source code I’d never seen, and set up secure credential storage in the macOS Keychain.

I watched this happen in real-time. Claude running commands, reading output, adjusting approach, explaining what it was looking for.

This is different from autocomplete. This is an agent that investigates problems systematically and fixes them while you watch.

The first antenna wiggle was satisfying in the way that hardware moments always are. Months of anticipation, reduced to a half-second of movement. Then the head moved. Then the body rotated. Then I asked it a question and it answered out loud.

I spent a few hours building the physical robot. Claude helped me start developing applications immediately.

The Apps

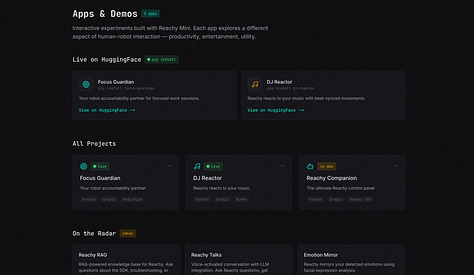

With the robot working, I wanted to build something beyond the default conversation app. Two ideas from my list stood out.

DJ Reactor

Makes the robot dance to music. It captures audio from the system, runs FFT analysis to separate bass, mid, and treble frequencies, detects beats in real-time, and translates all of that into robot movements.

Seven genre presets give it different personalities: rock mode headbangs, jazz mode sways smooth, electronic mode pulses with the bass.

I put on some music. The robot started moving. Not random twitching. Actual dancing. Head bobbing on the beat, body swaying with the bass line, antennas flicking on high frequencies.

There’s something absurdly delightful about watching a small robot groove to your playlist. My kid walked in, saw what was happening, and immediately started requesting songs.

Focus Guardian

Turns the robot into a productivity body double. It watches whether you’re at your desk using computer vision, tracks your presence during work sessions, nudges you if you drift away, and celebrates when you complete a session.

The idea comes from the body doubling technique that helps people focus: having another presence in the room, even a silent one, creates accountability.

The robot sits on my desk now. When I start a focus session, it breathes slowly (the antennas move in a gentle rhythm). When I leave my desk too long, it looks around like it’s wondering where I went. When I finish a session, it does a little victory dance.

It’s silly and it works.

Neither of these apps is going to change the world. That’s not the point. They’re fun. They demonstrate what the robot can do. And they went from idea to working prototype in hours, which meant I could actually use them during the build instead of finishing them someday later.

The Website

Building in public requires a place to put the public part. So Claude built that too.

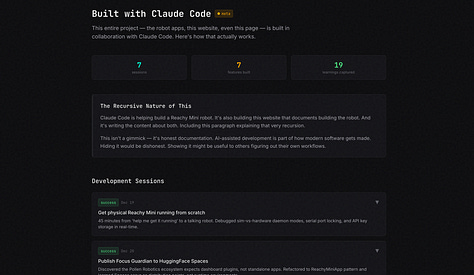

runreachyrun.com is the documentation site for this entire project. Not a landing page. The actual record of everything that happened.

What’s there:

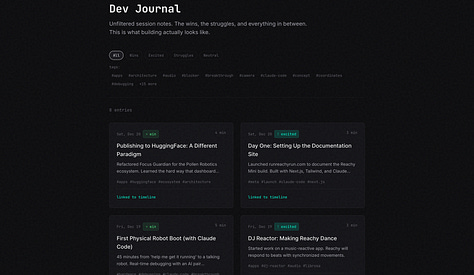

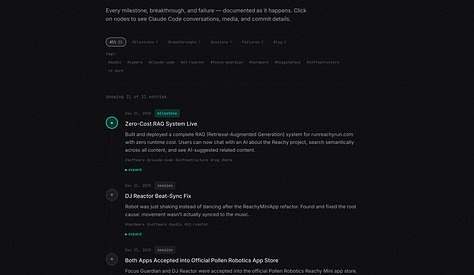

Timeline — Every milestone, breakthrough, and working session in chronological order. Each node expands to show commits, journal excerpts, and snippets from Claude Code conversations. You can filter by type (show me just the breakthroughs, or just the failures) or by tag. It’s searchable. It updates automatically when I add entries to the devlog.

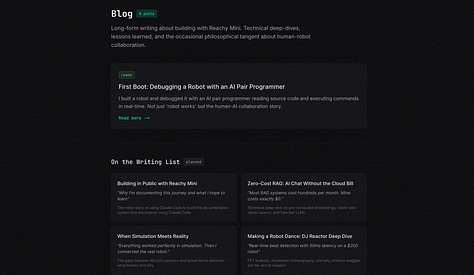

Journal — Detailed write-ups of development sessions. The full story of what worked and what didn’t. The debugging rabbit holes. The architectural decisions and why I made them. If the timeline is the outline, the journal is the full text.

Apps — The apps themselves with links to HuggingFace, install instructions, and the ideas still on the roadmap: Reachy Talks, Emotion Mirror, Twitch Plays Reachy. Some of these will get built over the holidays. Some might not. That’s also part of the public record.

Claude Page — A dedicated section showing how Claude Code contributed to the project, with expandable sessions containing actual prompts, insights, and code snippets. One of the sessions documents building the Claude page itself. The recursion is intentional.

AI Chat — Ask questions about the project and get answers grounded in the actual content. “How does DJ Reactor detect beats?” returns real information from the devlog, not hallucinated guesses. The whole thing runs on pre-computed embeddings and a free-tier LLM, so it costs nothing to operate.

Claude built this site while we built the apps. The devlog feeds the content pipeline. Write a stream note during a session, it appears on the timeline. The documentation happens as a byproduct of the work, not as a separate task afterward.

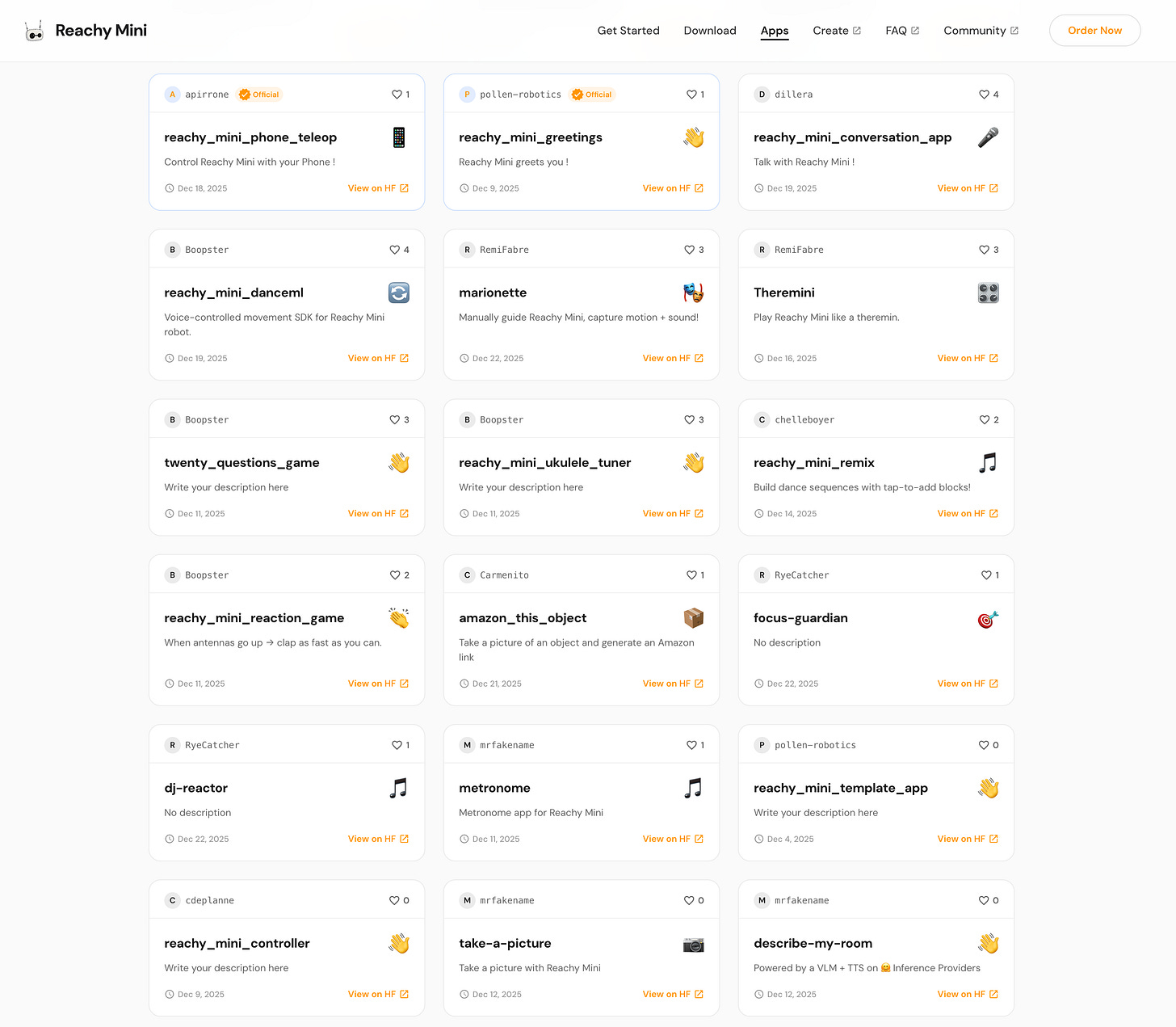

The Official App Store

Pollen Robotics maintains an app store for Reachy Mini. You submit your app, they review it, and if it meets their standards, it gets listed alongside their official apps. Anyone with a Reachy Mini can then install it directly from the dashboard with one click.

I decided to submit both apps.

The submission process required learning their ecosystem conventions. Apps need to follow a specific pattern. The naming has to be exact. README tags need specific values.

Claude handled the research, the refactoring, and the submission. Ran the validation tool, found the failures, fixed them, ran it again until both apps passed.

Both apps were accepted.

Focus Guardian and DJ Reactor are now in the official Pollen Robotics app store. Anyone with a Reachy Mini can install them.

Three days from first boot to official distribution.

I don’t know how long this would have taken without an agentic AI handling the SDK research, the packaging requirements, the trial-and-error of getting the submission format right. Weeks, probably. Definitely not three days while also building a documentation site and writing devlog entries.

The Holiday Build

Here’s where I actually am as I write this.

It’s the week before Christmas. I have two working apps on a real robot sitting on my desk. A documentation site that captures everything I’ve done and makes it searchable by anyone who wants to follow along. Both apps in an official app store. And a week of holiday break ahead with nothing scheduled except family time and whatever I feel like building next.

The boundary between building and using collapsed somewhere in the last three days.

I shipped while playing. The robot danced while I coded the next feature. The documentation wrote itself as a side effect of doing the work. I didn’t have to choose between making progress and capturing progress.

This is what agentic AI actually enables. Not replacing the builder. Amplifying what one person can do when the research, the boilerplate, the debugging, and the documentation are handled by something that works alongside you.

I keep finding new ways to push this. Last month it was building data pipelines. Before that, it was a semantic search system for my notes. Now it’s robotics. The tools keep getting better. The surface area of what one person can experiment with keeps expanding.

Build in public isn’t about showing polished results. It’s about letting people see the whole process: the debugging sessions at 6am, the wrong turns, the moments when something finally clicks. The agentic AI makes it possible to capture that process in real-time without slowing down the work itself.

Follow Along

The robot is going to keep moving. More apps are coming.

Reachy Talks is next on the list (voice-activated conversation with an LLM). Then maybe Emotion Mirror (the robot mirrors your expressions using facial analysis). My kid has requests. My wife has opinions about where the robot should live.

The holidays are going to involve some combination of building, dancing, and talking to a small French robot while eating too many cookies.

Everything gets documented at runreachyrun.com. The timeline updates as things happen. The journal captures the details. The apps go to HuggingFace when they’re ready.

If you want to see what happens when you let an agentic AI loose on a hardware project and document the whole thing, follow along. I’ll be the one debugging motor commands while my kid asks if the robot can do the floss.

Happy holidays. Go build something.

The apps are live on the official Pollen Robotics app store. The code is at github.com/BioInfo/reachy. The full build log is at runreachyrun.com.

This build is genuinely impressive! The part about documentation happening as a byproduct of the work, not after the fact, is somethign I've been trying to nail down in my own projects. I ran intosimilar friction with async work where the context switching between building and documenting kills momentum. Collapsing that boundary seems like the actual unlock here.