The Context Graph - AI’s Trillion-Dollar Opportunity

Why We’re Arguing About the Nouns While the Verbs Are On Fire

On December 22, 2025, Foundation Capital published what they’re calling AI’s trillion-dollar opportunity: Context Graphs.

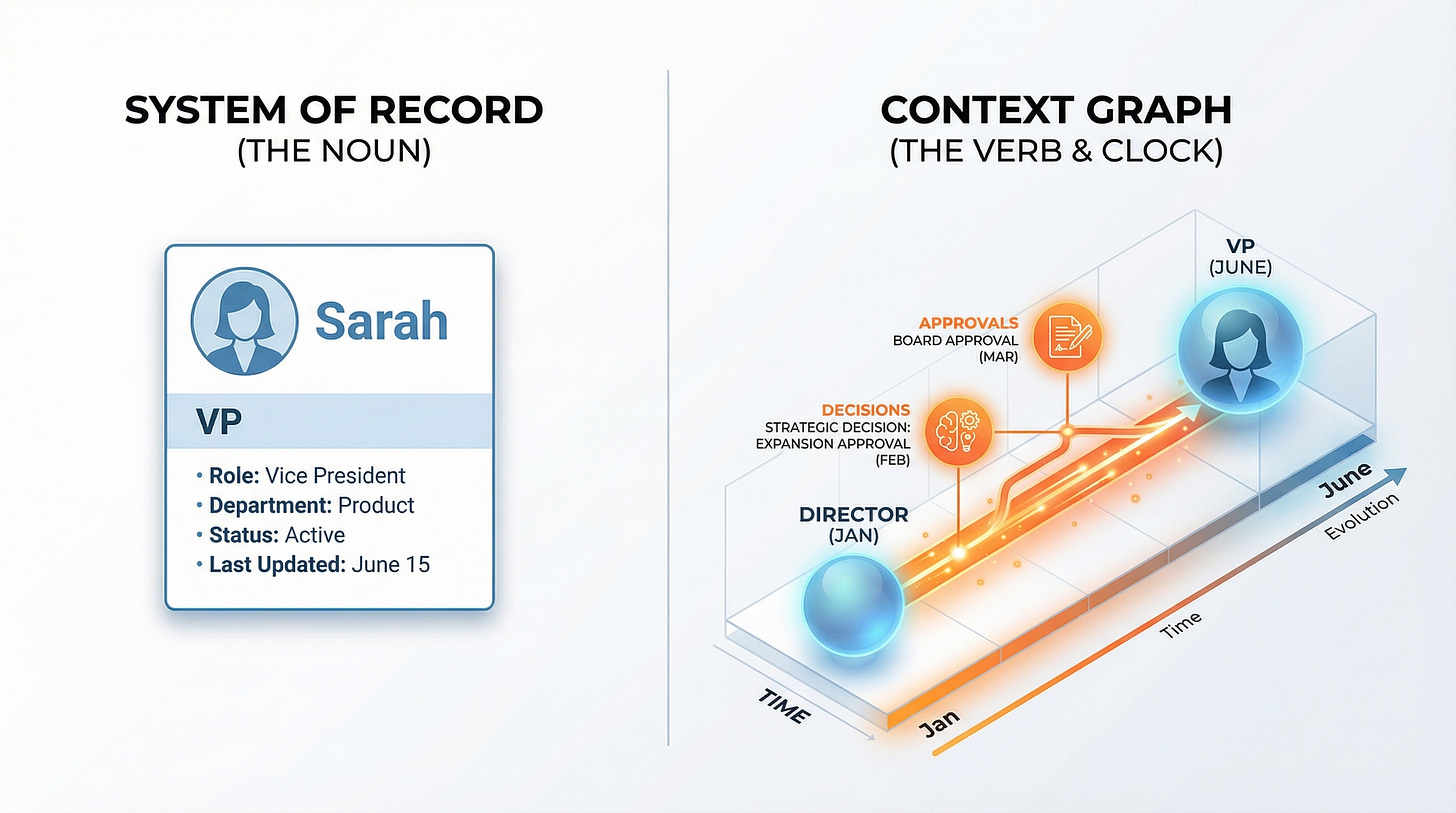

The thesis is simple and sharp. Jaya Gupta and Ashu Garg argue that enterprise value is shifting from “systems of record” (Salesforce, Workday, SAP) to “systems of agents.” The new crown jewel isn’t the data itself. It’s the context graph: a living record of decision traces stitched across entities and time, where precedent becomes searchable.

They’re right about the shift. What’s happening in enterprise software right now is the same pattern we saw when relational databases replaced flat files. The old systems stored what happened. The new systems need to capture why it was allowed to happen. That’s the unlock.

But here’s where the industry splits.

The moment you say “context graph,” two camps emerge with radically different answers to the same question: How do you model reality?

The Great Ontology Debate

Camp One: Prescriptive Ontology. Map the entities upfront. Build a semantic layer with object types, properties, link types, and action types. Define what a “Customer” is, what an “Order” is, how they relate. Get the schema right before the agents touch it.

Palantir exemplifies this approach. Their Foundry platform uses a three-layered ontology: a semantic layer for objects and relationships, a kinetic layer for actions and flows, and a dynamic layer for simulations and decision logic. It’s prescriptive by design. You don’t just throw data at it and hope. You model the domain, you define the primitives, you create a digital twin of your enterprise.

This works. Palantir runs some of the most complex data operations on the planet. Their ontology approach enables real-time AI integration, multi-modal data fusion, and defensible reasoning across massive enterprises. When you’re coordinating disaster response or managing defense logistics, you need that level of rigor.

Camp Two: Emergent Ontology. Structure will reveal itself. Run the agents, observe how they route work, let the graph “compile” from execution traces. The ontology emerges from behavior, not design.

This is appealing. It’s agile. It sidesteps the months-long schema design process and the inevitable arguments about whether “Contact” and “Lead” are the same thing. Just start working and let the system learn.

Both camps have a point. Both camps are also missing something.

Here’s what I see: You’re both arguing about the nouns. And while you’re debating what a “Person” or an “Account” looks like, your agents are failing because they can’t tell time.

The verbs are on fire. And without a clock, you can’t see them burn.

Stop Reinventing the Nouns

We’ve had Schema.org since 2011. Person, Organization, Event, Product. Microsoft’s Common Data Model covers enterprise domains. If your startup is spending engineering cycles “discovering” that a Deal has Contacts, you’re solving a problem that was solved before LLMs existed.

The real cost shows up when agents burn tokens on entity resolution. They see “Sarah Thompson” in Slack, “S. Thompson” in email, and “Sarah T.” in the CRM, and they have to infer these are the same person. Every time. That’s not intelligence. That’s waste.

The move isn’t “Prescribe vs. Learn.” It’s “Adopt foundations, then learn the nuances.”

Bootstrap with standards for the common stuff. Then let the system learn what matters in your domain. In pharmaceutical R&D, how a clinical trial relates to regulatory milestones and adverse event patterns. In genomics, how variant calls connect to phenotype observations and literature evidence. That’s where the learning budget should go.

The Real Problem: The Event Clock

If the entities are solved (or solvable), what’s actually missing? Time.

Most enterprise systems can tell you what is true now. Almost none can tell you what was true at 2:14 PM last Tuesday when a specific decision was made.

Your CRM knows Sarah is a VP. It doesn’t know she was a Director until June, and that the pricing exception approved in May happened before she had authority, which is why Finance flagged it as suspicious. That temporal gap turns into an agent failure. The system sees the current state, applies current rules, and misses the context that explains the exception.

This isn’t an edge case. It’s the default behavior of most enterprise data systems. They’re designed to answer “who owns this account now?” not “who owned it when this decision was made?”

Kirk Marple calls this the “Event Clock,” and he’s right. A context graph can’t just map entities and relationships. It has to track when things happened and what was true at that moment. The verbs (decisions, approvals, changes) only make sense if you know when they occurred.

“Sarah is a VP” is a fact.

“Sarah was a Director until June, then became the decision-maker for accounts over $500K” is context.

The difference matters when an agent is reasoning about historical decisions. Without the temporal layer, it hallucinates. It sees Sarah’s current title, applies it retroactively, and produces confident but wrong conclusions about who authorized what and when.

Three failure modes:

1. Stale Context. An agent analyzes adverse events for a clinical trial. The safety threshold changed two weeks ago, but the system only stores current state. The agent flags events using the old threshold. The medical monitor has to manually correct every assessment.

2. Missing Precedent. A principal investigator requests an off-label dose modification for a patient with comorbidities. The medical director approves it based on prior similar cases. Six months later, an agent reviewing protocol deviations flags it as a violation. It can’t see the approval chain or the clinical rationale. The precedent is invisible.

3. Temporal Collision. Two agents process the same biomarker data from different time snapshots. One updates the reference range. The other, working from cached lab normals, classifies results using the old range. Patients get contradictory clinical flags. No one notices until an auditor asks why the same value triggered different actions.

The technical foundation exists. But it’s not standard in context graphs yet. Most systems treat time as a second-class citizen: timestamps on records, logs for audit trails, but no real ability to reason about what was true when.

Captured Reasoning: The Trillion-Dollar “Why”

This is where Foundation Capital’s thesis gets interesting. The unlock isn’t just storing data better. It’s capturing decision traces.

Right now, enterprise systems record outcomes. A deal closes at a 40% discount. A support ticket escalates to engineering. A finance reconciliation requires manual override. The system logs what happened. It doesn’t capture why it was allowed to happen.

The reasoning lives in Slack threads, Zoom calls, email chains, and hallway conversations. A VP explains why the discount made sense given the customer’s multi-year commitment and strategic value. A support manager describes why this particular bug warranted escalation despite not meeting the severity threshold. A finance controller documents why the override was justified given the vendor’s payment structure.

That context evaporates. The CRM stores the discount. The ticketing system stores the escalation. The ERP stores the override. But the reasoning never enters the system of record. It exists only in the memories of the people involved and in unstructured communication channels that agents can’t reliably search or understand.

A true context graph captures the instrumentation of the choice.

When an agent encounters a similar situation later, it doesn’t just see data. It sees precedent. It doesn’t just see “a VP approved a 40% discount,” it sees “VP Sarah Thompson approved a 40% discount for Customer X because they committed to a three-year contract and became a reference customer, which met our strategic partnership criteria even though it violated standard pricing policy.”

That’s the difference between a policy violation and a searchable exception.

This transforms how agents reason. Instead of applying rigid rules and flagging every deviation, they can pattern-match against historical reasoning. They can propose similar exceptions when the conditions match. They can surface relevant precedents to human decision-makers. They can learn what “strategic value” means in practice, not just in a policy document.

Foundation Capital’s “replayable lineage” concept captures this. The context graph becomes an authoritative record not just of what happened, but of why decisions were made, who had authority, what context they had, and what reasoning they applied.

The value compounds over time. Every exception becomes training data. Every override becomes a case study. Every decision trace makes future decisions faster and more consistent. The graph doesn’t just store history. It makes history useful.

This is why systems of agents will win. They sit in the execution path. They see the decision being made in real time. They can capture the reasoning at the moment it’s articulated, not reconstruct it later from fragments.

The context graph becomes a natural byproduct of agentic work, not a separate documentation burden.

What Wins

The opportunity isn’t in the ontology debate. It’s in building systems that capture what’s actually happening when decisions get made.

Three requirements:

Use existing standards for the basics. Person, Organization, Event. Don’t reinvent them. Spend your engineering budget on what’s unique to your domain.

Make time a first-class citizen. Build the clock into the foundation. Store what was true when decisions were made, not just what’s true now. Answer “what did the system know at the time?” as easily as “what does it know now?”

Capture reasoning in real time. When someone approves an exception, when a policy gets overridden, when a judgment call happens—capture why. Not as documentation afterward, but as part of the decision itself.

The companies that win will be the ones present when decisions happen, not the ones analyzing them later. Systems of agents, not systems of record.

Palantir saw this early. Their focus on operational decision-making, not retrospective analysis, gave them an edge in complex environments. The new wave of agentic systems has the same structural advantage, with faster iteration and lower barriers to entry.

The Bigger Picture

Foundation Capital’s thesis is correct. Context graphs are the next platform shift in enterprise software. But the debate about how to model them misses the deeper challenge.

The hard part isn’t the graph. It’s the clock.

The hard part isn’t the entities. It’s the temporal validity.

The hard part isn’t storing decisions. It’s capturing why they were made.

Get those right, and the context graph builds itself. Get them wrong, and you’ll have a beautiful ontology that can’t answer the questions that actually matter.

If you’re building in this space, here’s the test: Can your system tell me what a specific agent knew at 2:14 PM last Tuesday when it made a specific decision? Can it show me the precedent for an exception? Can it explain not just what happened, but why it was allowed to happen?

If the answer is no, you’re not building a context graph. You’re building a better database.

And databases are not where the value is moving.