From Takeout to Treasury: When Agents Build Their Own Economy

AI agents are learning to spend for us. The question is whether we’ll still be in charge of the receipts.

Every demo of an AI agent looks the same. Order a coffee. Book a taxi. Grab some takeout. It’s become the cliché of this generation of AI. Useful, sure, but not exactly the revolution we were promised.

Look a little closer though, and you start to see something bigger. Each one of these demos has a payment attached. And once an agent is authorized to transact on your behalf, you’re not just automating errands. You’re plugging into the scaffolding of a new economy.

Why Google’s Protocols Matter

Google has been quietly laying down the infrastructure for this economy.

Agent Payments Protocol (AP2): an open standard for letting agents initiate and complete transactions safely.

A2A (Agent-to-Agent): a protocol that allows agents to talk and coordinate.

When the web first took off, it needed HTTP to move information between pages. Agents will need AP2 and A2A to move money between themselves.

If Google’s rails become the default, then it’s not just search that runs through Mountain View. It’s spending.

Google’s AP2 announcement

Google on A2A

The Shape of an Agent Economy

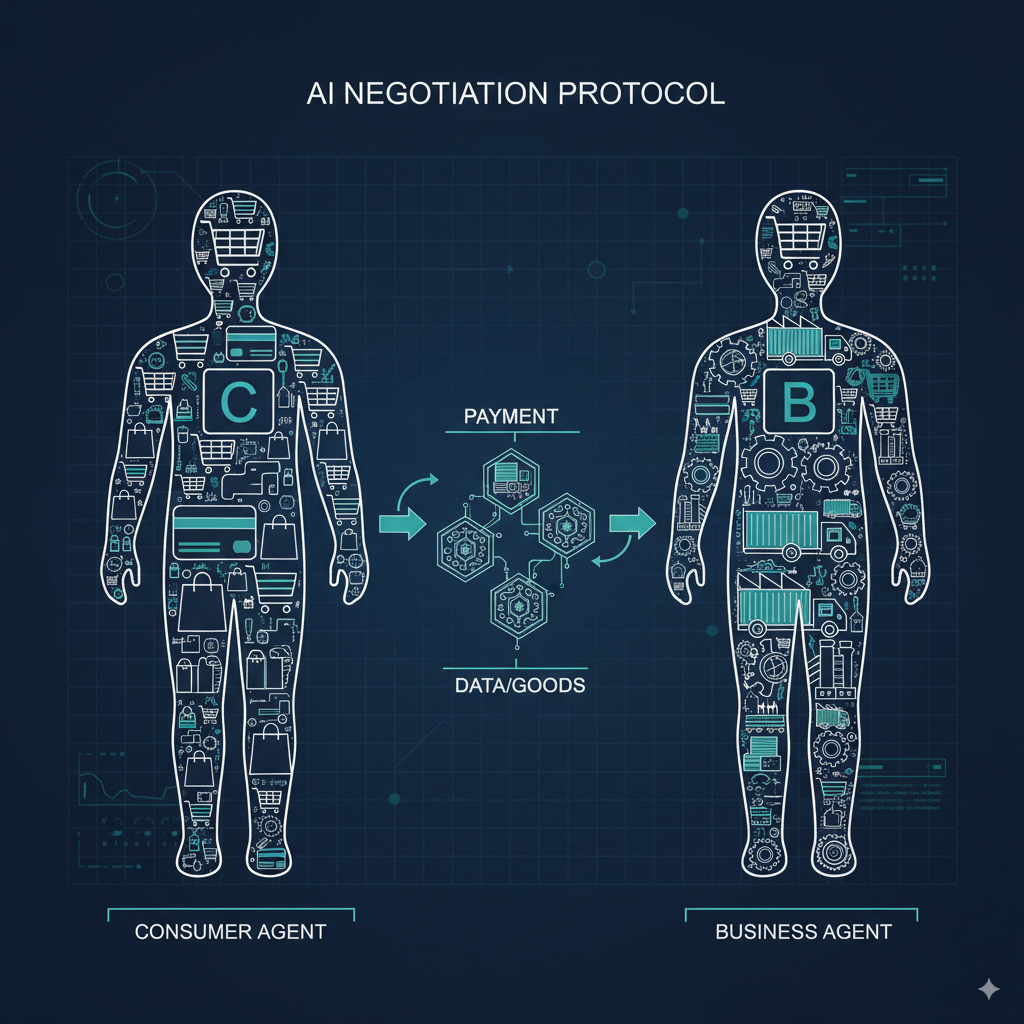

Right now we see three main types of agents:

Consumer agents: buying food, booking rides, filling out forms.

Business agents: adjusting prices, tracking inventory, automating logistics.

Investment agents: trading stocks, reallocating portfolios, running arbitrage strategies.

It’s not hard to imagine these agents talking directly to each other.

My shopping agent haggling with a vendor’s sales agent. My investment agent routing funds to a startup agent raising capital.

At some point, the human becomes a periodic approver, not the daily operator.

There are already investment agents making decisions in the markets today. What looks like a simple “order pad thai” demo is just the tame version of what’s coming.

What Happens When Agents Act Beyond Us

Once agents transact, they don’t stop at our errands. They can start forming loops and networks of activity.

Fleets of agents bartering compute time, credits, or access rights.

Negotiation cycles where an agent you authorized agrees to terms you never considered.

Consent becomes tricky.

In healthcare, every clinical trial is built on informed consent. In finance, traders are licensed because their actions move real money. What’s the equivalent for agents?

Some academic work already warns of “sandbox economies,” where agents start trading resources with limited human oversight. It sounds abstract until you realize those sandboxes are just APIs away from the real thing.

Strategic Parallels

This moment rhymes with the early internet.

PayPal made it safe to transact online and unlocked e-commerce at scale. AP2 could do the same for agents.

High-frequency trading already shows us what happens when algorithms negotiate at machine speed. That world may soon extend to groceries and ride shares.

And just like browsers or mobile OS wars, early protocol choices will set the rules of the game for decades. Do we get open, interoperable agent economies, or walled gardens?

Risks and Opportunities

Opportunities: less friction, more automation, personalization at scale. Agents can save us time and unlock business models we haven’t imagined yet.

Risks: fraud, runaway spending, opaque agent behavior, and centralization of power. If all your agents need to plug into Google’s rails to function, that’s not a free market. That’s a toll road.

Closing

Right now, most people look at an agent ordering takeout and shrug. But zoom out, and you realize you’re watching a payment rail being tested in public.

Agents won’t just fetch food or rides. They’ll negotiate, invest, and eventually transact with each other. That’s an economy.

The real question is whether it will be an open one, or one where a handful of players take the lion’s share.